Expansion Vessel Failures: Symptoms and Replacement

A failing expansion vessel won't announce itself with a dramatic breakdown. Instead, you'll notice your boiler pressure gauge climbing above 3 bar when the system heats up, or find yourself topping up pressure every few days. These quiet signals indicate a component that's lost its ability to manage thermal expansion, and ignoring them leads to relief valve discharge, system shutdowns, and potential boiler damage.

Expansion vessels are replaced weekly across commercial and residential heating systems. The pattern is consistent: most failures stem from membrane rupture or air charge loss, both creating pressure instability that stresses every component in the system.

How Expansion Vessels Actually Work

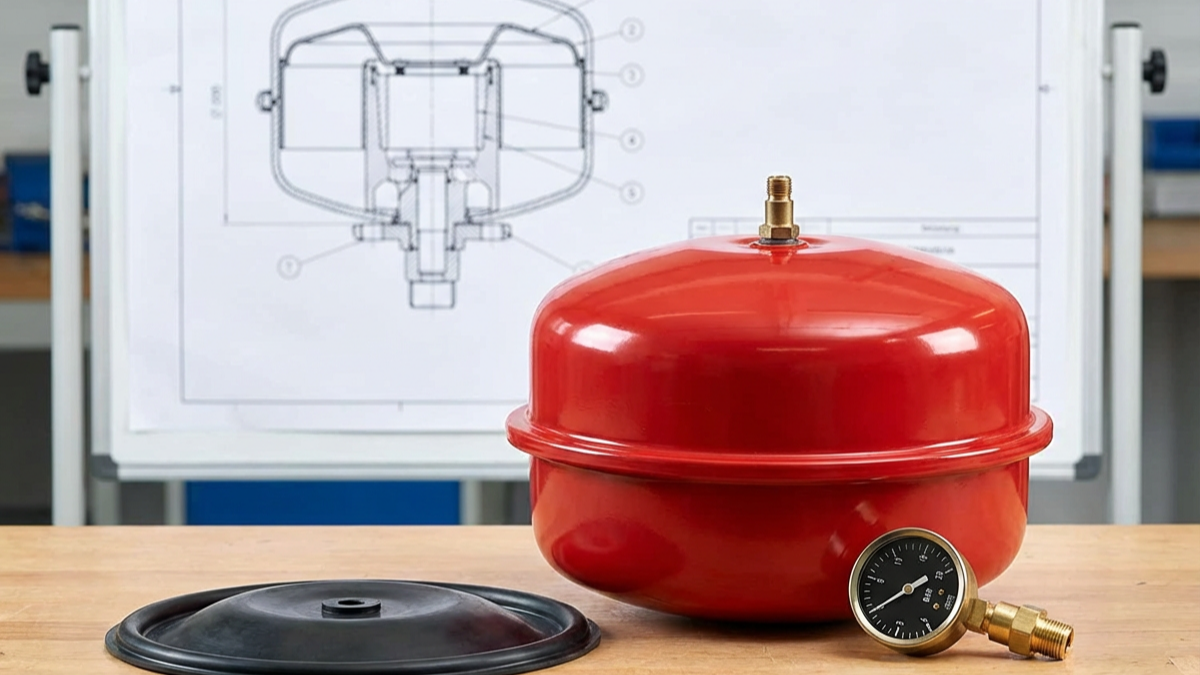

When water heats from 10°C to 80°C, it expands by roughly 4%. In a sealed heating system, this expansion needs somewhere to go. The expansion vessel provides that space through a flexible rubber membrane separating two chambers: one connected to the system water, the other pre-charged with nitrogen or air.

As water heats and expands, it compresses the gas cushion. When the system cools, the compressed gas pushes water back into the circuit. This cycle maintains stable pressure between roughly 1.0 and 2.5 bar during normal operation.

The pre-charge pressure, typically 0.5 to 0.8 bar below the cold system pressure, determines how effectively the vessel absorbs expansion. A 12-litre vessel on a 100-litre system with 1.0 bar cold pressure needs approximately 0.5 bar pre-charge. Get this wrong, and the vessel can't do its job.

Five Symptoms That Confirm Vessel Failure

Pressure rises above 3 bar when heating runs. This is the clearest indicator. A functioning vessel absorbs expansion smoothly. When the membrane fails or the air charge depletes, expanding water has nowhere to go except against the pressure relief valve's set point.

Pressure drops below 0.5 bar within 48 hours of filling. If you're not seeing visible leaks but pressure keeps dropping, water has likely crossed the membrane into the air chamber. Each heating cycle pushes more water through the failed membrane, displacing the gas charge completely.

Relief valve discharges during heating cycles. That puddle under the external discharge pipe isn't condensation. When system pressure exceeds 3 bar (the typical relief valve setting), the valve opens to prevent damage. This shouldn't happen with a working expansion vessel.

The boiler short-cycles or shows pressure faults. Modern boilers monitor pressure constantly. Rapid pressure fluctuations trigger safety shutdowns. Commercial systems cycle off 15-20 times daily because a failed expansion vessel creates pressure spikes that the boiler interprets as faults.

The vessel sounds waterlogged when tapped. A healthy vessel sounds hollow when you tap the lower half; that's the air chamber. A dull, solid sound indicates water has filled the gas side through a ruptured membrane.

Why Vessels Fail (and When to Expect It)

Membrane fatigue causes 70% of the failures diagnosed. The rubber diaphragm flexes thousands of times annually. After 5-8 years in residential systems or 3-5 years in commercial systems with frequent cycling, the membrane develops microscopic tears. Water seeps into the air chamber, gradually eliminating the gas cushion.

Air charge loss through the Schrader valve accounts for another 20% of failures. The same valve design used in car tyres doesn't always seal perfectly under constant pressure. A vessel losing 0.1 bar annually might work adequately for years before crossing the threshold where it can't absorb expansion effectively.

Corrosion punctures the vessel wall in systems with poor water treatment. Failed vessels show rust perforation from the inside, preventable with proper inhibitor concentration and pH control.

Incorrect initial pre-charge causes premature failure. An undersized vessel or wrong pre-charge pressure forces the membrane to over-extend with each cycle, accelerating fatigue. A 12-litre vessel on a 200-litre system will fail quickly because it's working beyond its design capacity.

Testing Before You Replace

Check the pre-charge pressure first. Isolate the vessel from the system (close the isolation valve or drain the system to zero pressure), then press the Schrader valve. If water sprays out, the membrane has failed; no further testing is needed.

If air releases, attach a pressure gauge. The pre-charge should read 0.3-0.5 bar below your cold system pressure. A 1.0 bar system needs 0.5-0.7 bar pre-charge. Below 0.3 bar indicates air loss; you can re-pressurise, but if it drops again within a month, the valve seal has failed.

Measure the system pressure cold, then run the heating to the maximum temperature. Pressure should rise 0.5-0.8 bar in a residential system, 0.8-1.2 bar in commercial systems with larger water volumes. Rises exceeding 1.5 bar confirm insufficient expansion capacity.

The bounce test works on accessible vessels. With the system cold and pressurised, tap the vessel sharply. A working vessel resonates briefly. A waterlogged vessel produces a dead thud with no resonance.

Sizing the Replacement Correctly

Match the vessel capacity to your system volume and temperature differential. The formula is straightforward:

Vessel volume = (System volume × Expansion factor) / ((Pmax / P0) - 1)

System volume: 100 litres Expansion factor: 0.04 (4% for 10-80°C) P0 (pre-charge): 0.8 bar absolute (1.8 bar total) Pmax (relief valve): 3.0 bar absolute (4.0 bar total)

Vessel volume = (100 × 0.04) / ((4.0 / 1.8) - 1) = 3.3 litres minimum

8-12 litre vessels are installed on most residential systems under 150 litres, providing a safety margin for calculation variations and future system additions. Commercial systems need professional calculation based on actual water content, operating temperature, and static head. Heating and Plumbing World supplies expansion vessels from reliable manufacturers like Altecnic Ltd for both residential and commercial applications.

Undersizing by 50% might work initially, but accelerates membrane fatigue. The membrane reaches full extension every cycle, flexing through its entire range rather than working in the middle third of its travel.

Replacement Process That Prevents Comebacks

Drain the system or isolate the vessel completely. Any residual pressure prevents proper installation and can damage the new vessel's membrane during connection.

Check the pre-charge before installation. New vessels typically arrive at 0.75-1.0 bar. Adjust to match your system requirements, 0.5 bar below cold operating pressure. This five-minute step prevents 90% of "vessel failed again" callbacks.

Install with the connection pointing down. The membrane settles correctly with water entering from below. Wall-mounted vessels should have the connection at the bottom; floor-standing vessels work in any orientation, but the bottom connection remains best practice.

Use a proper sealing compound rated for heating systems. PTFE tape can shred and block the connection path. Jointing compound or pre-applied sealant on compression fittings works best. Quality fittings ensure reliable connections during expansion vessel replacement.

Refill slowly and vent thoroughly. Trapped air in the system reduces effective water volume, throwing off the expansion calculations you just made. Bleed all radiators and high points before setting the final pressure.

Set cold pressure to 1.0-1.2 bar on residential systems, adjusted for building height (add 0.1 bar per storey above ground). Run the system to full temperature and verify pressure peaks below 2.5 bar. If it exceeds this, either the vessel is undersized or the pre-charge needs adjustment.

When to Add Rather Than Replace

Systems above 200 litres often benefit from additional expansion capacity rather than replacing an undersized original vessel. Secondary vessels are added to commercial systems where replacing the original required extensive pipework modification.

Connect the second vessel to any convenient point on the system, before the pump is ideal, but anywhere on the return side works. The vessels share the expansion load automatically through hydraulic pressure equalisation.

Pre-charge both vessels identically. Mismatched pre-charges cause one vessel to handle most of the expansion, whilst the other sits idle until pressure rises significantly.

This approach works particularly well on system extensions where the original vessel becomes undersized after adding radiators or zones. A 12-litre original vessel plus an 8-litre addition handles a system that's grown from 100 to 180 litres without removing the working original.

Common Installation Mistakes That Cause Early Failure

Installing with the system pressurised compresses the membrane against the water connection before any water enters. This pre-loads the membrane asymmetrically, creating a weak point that fails within months.

Forgetting to check pre-charge means you're installing blind. "New" vessels from distributors read anywhere from 0.3 to 1.5 bar, a range that is wrong for almost any application.

Mounting vessels in unheated spaces exposes them to freezing. The water side connects to the system and won't freeze, but if the ambient temperature drops below zero, the vessel body can crack. Garage and loft installations need insulation or relocation.

Over-tightening compression fittings distorts the vessel connection, preventing the membrane from seating properly against the internal mounting point. Tighten to resistance plus one quarter turn; the brass fitting does the sealing, not your torque.

The Cost of Delayed Replacement

A failed expansion vessel stresses every component in the system. Relief valve discharge cycles wear the valve seat, leading to weeping that becomes continuous dripping. Relief valves are replaced on 40% of systems where the expansion vessel failed more than six months before repair.

Pressure fluctuations stress the heat exchanger, particularly on combination boilers where the domestic hot water side operates at higher pressure. Repeated pressure spikes accelerate heat exchanger fatigue and can cause premature pinhole leaks.

Pump seals wear faster under pressure cycling. The mechanical seal operates within a design pressure range; exceeding this range repeatedly breaks down the seal faces and allows weeping around the pump shaft. High-quality pumps from Grundfos or Lowara resist pressure cycling better, but even these suffer without proper expansion vessel function.

The boiler's pressure sensor, a diaphragm-based component similar to the expansion vessel itself, degrades under constant fluctuation. Sensor drift causes nuisance lockouts that technicians misdiagnose as electronics faults, leading to unnecessary control board replacements.

Conclusion

Expansion vessel failure creates a cascade of pressure problems that stress your entire heating system. The symptoms are clear: pressure climbing above 3 bar during heating, frequent pressure loss, relief valve discharge, or that telltale waterlogged sound when you tap the vessel body.

Testing takes ten minutes: check the pre-charge pressure with the system isolated, measure the pressure rise during a heating cycle, and press the Schrader valve to confirm the membrane hasn't ruptured. These simple checks confirm whether you need expansion vessel replacement or just re-pressurisation.

Size the replacement for your actual system volume with a safety margin, set the pre-charge 0.5 bar below your cold operating pressure, and install with the connection pointing down. These steps prevent the premature failures seen when vessels are rushed into service without proper preparation.

Address expansion vessel problems within weeks, not months. The £80-150 cost of expansion vessel replacement is minor compared to the relief valve, pump seal, and heat exchanger damage that develops when pressure cycling continues unchecked. The system you save is the one you maintain before small problems become expensive repairs. For expert guidance on expansion vessel replacement and sizing, contact us for a professional assessment.

-

-